The Progressive Post

The European “historical” Elections 2024, dramatic moments and moderate outcomes

The European “historical” Elections 2024, dramatic moments and moderate outcomes

The European Elections are always labelled as historical. Partially because every five years, when they take place, the Union finds itself in yet another crunch moment. And there is always the hope that they will be a moment to deliberate publicly how to proceed, and to receive a clear political mandate to advance with the integration process. This expectation never ceases, despite everything that is said about this vote, which is described as a ”second order one’,’ and as a sum of 27 national elections.

This type of idealism should is neither as naive nor futile. First, because it is the engine behind a great mobilisation. The europarties, trade unions and NGOs feel compelled to reflect on the state of the union and to propose new policy initiatives. Evidently, the outreach of these efforts is not unlimited, some may consider them as mainly directed towards the EU policy-making bubble, but these are important deliberations and moments of political creativity. Secondly, because this is among the few times when Europe plays an important role the national public debates. These are the periods in which experienced stakeholders’ attitudes towards the future of the Union truly matter. And even more so, these are periods when the question who should represent the citizens on the different levels of governance is discussed, along the how. , In these moments, it is being discussed, in very practical manner, what can and cannot be done by MEPs. Thus, even if short-lived, and even if these periods are cynically overlooked by a focus on the subsequent election results (with low turnout in particular), these are the moments when European democracy is exercised. The campaign of 2024 was no exception.

Still, before this year, there were many of hopes for the campaign to be different from the previous ones. Primarily, because it seemed that the EU was emerging after the sequence of crises, which scope and prolific natures had combined into a polycrisis. In past mandates, the EU had to deal with the persisting (still) consequences of the global financial crisis of a decade earlier, face the global pandemic and its effects, saw a war erupting at its doorstep with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and also saw its vulnerabilities exposed with the crisis of supply chains and the cost-of-living crisis. In parallel, it had to persevere against the tendencies of the centrifugal forces and protect the values on which it has been build, defending internally democracy and the rule of law. These are just several headlines, which marked the period in which, despite everything, the EU was supposed to transform – responding to citizens’ calls to become an entity that contributes to such decisive fights as that against climate change. In the early months of 2024, in the pre-run up of the European elections, it seemed that the Union succeeded. Many of its actions were both noticed and valued, as the approval rates for what the Union has been doing were growing. Even more so, in times when so many voters were expressing a sense of disempowerment, disenchantment and disconnection from the ‘traditional politics’, the EU institutions were considered more trustworthy than the national ones. These were important signals, giving hope that despite the surveys pointing to the unprecedented rise in force of the radical right, there was a solid ground for the pro-European, mainstream forces to compete on.

With the 2024 campaign over and with the last ballots counted by, it is worth to reflect what kind of European elections these were in the end. And what their outcomes signify, especially when it comes to the political prospects for the immediate three months of the negotiations (about the ‘top jobs’ and workplan) and consequently, for the five years of the mandate. There has been no doubt that the EU will have to face some unprecedented existential dilemmas such as when and how to enlarge, and how institutionally reform to grow in strength. Hence analysing what happened may be instructive not only as an explanation of the past, but also as a way of trying to anticipate what may come next.

In that spirit, these short ten takeaways:

- Paradoxically, the one trend that europeanised the campaign was a surge of the radical right across the continent

The results of the national elections in 2022 and 2023 showed that right-wing radical groups were growing in power. Citizens across the continent were casting their support behind these parties for very diverse reasons and amid a complex context (described earlier), which has been prompting a more general feeling of instability, disempowered and anxieties of different sorts, the narrative of the far right was finding an additionally fertile ground indeed. Consequently, the expectation ahead of the European elections was that the radical right would note unprecedented gains and constitute a real threat to the future of the European integration. The advancements that the parties belonging to that political leaning have been noting made the majority of the headlines and framed a vast number of the debates.

As a result, this was the main common European topic of the campaign, which effectively consumed the spotlight. But, in the end, while the right-wing radicals did well, they did not do well enough to truly upset the existing composition of the European institutions. Their gains are not sufficient to make a coalition of the traditional right and radical right the only viable in the EP. What is more, the right-wing radicals have never represented a political monolith and already in the past have been troubled, whenever trying to unite forces into one political family backing a common project. So, they are bound to play a disruptive role in the decision-making processes, but at this moment they are not in a position to upset the trajectory of the integration processes. Especially, seeing that negotiations, rather transactional in nature, about who will sit in which political group and with an ambition to what role, are still ongoing.

- The pro-Europeanism found its way to prevail, but the challenge remains to make the political narratives connect in the era of polarisation

Although the European elections are considered to be second order elections and hence see voters make their decisions based on other issues than those directly connected to the EU, there is for several years now a tendency for some issues to be more present and hence frame the debates. Although it was unanticipated, in 2014 the controversy that mobilised voters in Athens and in Aachen was the question of TTIP. In 2019 it was a demand to act against climate change and to resolve the issues around migration. And in 2024, it was the set of socio-economic questions connected with the cost-of-living crisis. With that in mind, there is a valid question why this did not swing the pendulum decisively towards Social Democrats – who according to the exit polls only received 135 out of 720 seats. This, in absolute numbers, represents a small loss. In other words, in 2019 we did better than expected, while in 2024 we did not do as bad as anticipated.

This is a query, especially that the top candidate of the PES family was Nicolas Schmidt, the EU Commissioner for Jobs and Social Rights – who has been a symbol of Social Europe and the progress that has been championed in the past mandate amid the polycrisis. And he did a superb job, campaigning in more than 40 cities across the Union and promoting the manifesto The Europe we want: social, democratic, sustainable that PES adopted at the Congress in Rome in March. The answer may be two folded. The first part of it would be the more traditional assessment that though the programme was clear, the difficulty was in creating narrative that would connect. The second, looking at the unprecedented success in these elections of Raphael Glucksman and the PS in France, as also at the result in countries such as the Netherlands, is that the pro-Europeanism and progressivism can prevail, in case it is considered THE clear alternative to the right extreme. And hence, when it positions itself as unique and as a counterweight to the growing, and, for the moment, unavoidable polarisation.

- The political map of Europe is a subject of tectonic shifts, while some regions are exceptional due to particular tendencies

Reviewing the outcomes of the European elections, one notices the variety of the colours that stand for the different political family becoming a winner or runner-up in the respective EU member states. Analysing it closer, it is hard to deny that the EPP family, which had been troubled and diagnosed with a crisis one or two years ago, bounced back. It is also visible in the gain in seats, even if sceptics would say that the numbers do not necessarily reflect the positioning in the countries. Still, on the map of winners, red is marked for two countries: Sweden and Portugal. However, one should not overlook Romania, where PSD co-founded a successful electoral coalition. Diving into details, one finds that the performance of Social Democrats has been unequal.

Indeed, there is a certain regionalisation of the results emerging. If to generalise, the centre-left sustained a status quo in the north, noted gains in the broadly defined south and was very troubled in Central and Eastern Europe. And when it comes to the latter, this is also the region with eight countries where the lowest turnout in the EP elections was noted, around 30 per cent. Evidently, there are, as it always is in case of the second order elections, specific reasons which led to these results within the respective countries. And it is not possible to say that this is a question of the model these parties adopted in 1990s, because there is a diversity of histories and traditions even among two neighbouring countries – for example CSSD (now SocDem) and MSZP. Nevertheless, the weak results and the fact that there will be only one or no S&D-MEPs from some of the CEE states calls for a broader discussion about the ‘Eastern discomfort’. It is never too late for investing in it, especially seeing that on the other hand, within the same movements, parties that had been seen as doomed and done – such as PASOK and PS France did well.

- The EU has been fighting for democracy and the rule of law, but protecting public sphere starts from individual level of commitment

The 2024 campaign was also qualitatively dissimilar to its predecessors due to a very different nature of the confrontation between the clashing political views. It was shocking indeed to hear about the cases of aggression and violence, with a symbolic one among them being the brutal assault on the SPD MEP and candidate Matthias Ecke. This and many other examples point to the growing brutalisation, which cannot be addressed only as a by-product of the growing polarisation. It is a question of an amassed revolt against the political culture and the core values on which the EU was established. The phenomena are simply unacceptable and should be condemned with full force, but a straightforward reaction does not seem to address the entire complexity of factors and circumstances from which violence in politics derives.

Consequently, there should be no ‘turning the page’ just because the campaign is over. The issue has not vanished and there is a moral obligation not to let forget about the attacks. That said, there is a question on what can be done to de-root these practices and prevent their normalisation. One path is the EU and what it can do to protect and promote democracy. The definition here requires expansion, as it should seriously consider the digital sphere in which even more brutalisation has been recently taken place. Partially also due to the intense disinformation and baiting campaigns. The scale of these is growing and indicative here is that one third of citizens in countries such as Sweden recognise being exposed to it. The other path is about bringing democracy back to the level of an individual issue, as many of the campaigners pointed to the fact that the EU fight for rule of law was considered noble and effective by voters they talked to, but still distant and not personally relatable. That has to change.

- Localising Europe mattered, but there was no space for a real debate on the Future of a European debate

The fact that the European elections are considered second-order is usually a negative characteristic, as next to all aspects already explained earlier, it also means often that it is not the EU or the EU-related issues that are debated during the campaign. In 2024, there was however a great mix of tendencies. On one hand, the second order meant that the local dimension played a role and in some cases the possibility of voting for locally well know candidates as representatives on the EU level was very welcome. That was the case for example in Italy, where PD reached a very good result also thanks to the popular mayors who stood on the lists. On the other hand, there has been still close to no debate about the issues that should shape the future of the EU. The focus remained on national battles, seeing some of the parties politically sandwiched. And that made the Social Democrats in some countries, like it was the case for Nowa Lewica in Poland, entrapped in a narrative of a positive, but transactional version of the EU (‘what the EU can do for the EU’).

The consequences of that are profound. First, because the EU is hoping to enter a period in which both its size and its shape should be revised. For both the enlargement and the treaty changes, there needs to be also a momentum inside of the member states. That is a condition sine qua non not only for the ratification, but also for the democratic legitimacy and citizens’ endorsement for these processes. What happens when there is a lack of these, one can anticipate by recalling for example the failure of the so-called Constitutional Treaty. Secondly, this created a situation in which the voices criticizing some of the achievements of the previous mandates were heard loud and clear. The examples of them were negative assessments of the European Green Deal, being seen as too much, too fast. With that and some other initiatives that belong to the proud Progressive legacy of the past mandate, Social Democrats on the EU level will need a carefully crafted strategy to be able to defend the progress achieved – without being pushed into defence corners of the debates.

6. These European elections mattered especially for the national level, bringing shifts in power across the European Council table

Yet again referring to the particular character of the European elections, they are seen by many voters as a peculiar referendum that allow them to express their opinion about their country’s governments or (less frequently) one of the issues dominating the national debate at the given moment. This has been frequently the reason why some of the smaller parties reach incomparably high results in the EU elections. But in 2024, the scale of this phenomenon was much greater than in the past. Not only because in some countries there were multiple elections combined together (such as it was the case in Hungary, Belgium, Ireland or Bulgaria, which voted nationally for the sixth time in just two years noting an excessive voter’s fatigue).

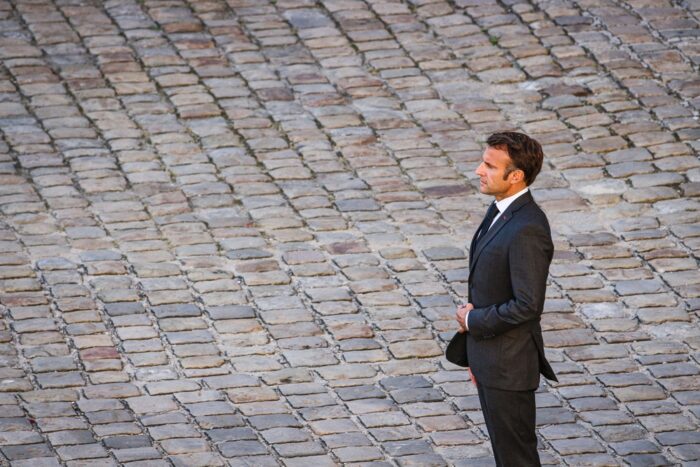

In particular, for the countries of the so-called Weimer Triangle, it was a situation in which many citizens used their ballots to express what they think about their governments. Here, Donald Tusk as the prime minister and leader of the coalition in Poland was proclaimed a great winner, Olaf Scholz and his coalition were weakened, and the standing of president Emmanuel Macron evaluated as a disastrous prompting him to call snap general elections the same night. The Weimer Triangle saw therefore signals from green through yellow to red, with that already changing somewhat at least temporarily the informal orientation of Europe on the political Berlin-Paris axis. This is part of a bigger picture, as in parallel Victor Orbán found himself in a challenging context, while Giorgia Melloni solidified her position. All in all, this is an indication of dynamic circumstances, to say the least, and that those who claim to have emerged victorious according to the exit polls may not have yet all the questions of the new mandate sorted by default.

7. The European Parliament was elected over four days, but it will take the next four months for the EU to move on

The results of the European Parliament’s elections leave the assembly with a possibility to continue with the well-known culture of compromise and grand coalition of the ‘traditional’ political groups. The EPP representatives, who proudly took the stage on the election night, including their top candidate and current president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, claimed victory and reassured that they want to proceed within the alliance of the pro-European forces. And such a constellation would indeed amount to the necessary majority, even while Liberals and Greens noted many electoral losses. Social Democrats, who retained their position as the second largest political family in the EP, answered that their participation is not unconditional and that the clear red line is no agreement with radical and far right.

These statements are consequential. First, this means that the process that some observers would like to see as a straightforward one and even try to stretch to finally recognise the institution of the top candidate (from Article 17 of the Lisbon Treaty) may become turbulent at any moment. The percentage of seats represented by the coalition that emerges in the EP does not mirror their respective weight in the European Council. And this is the attention point, as the rebalancing within the intra-institutional process may be a tricky act. Secondly, while the pro-European coalition is now at the first steps of the negotiation process, it will this time pay particular attention to not only the top jobs distributions, but also the issues at stake. This is a great progress towards the culture of grand coalition agreements (known for example from Germany). An important step was made in this direction in 2019, when the political groups sent letters to the Commission president-designate, outlining their conditions for granting her the support. This time the negotiations are expected to be more diligent. And Social Democrats have all the interest in these, especially that they have to protect themselves from being vulnerable – which may be the case, if they are part of the coalition agreeing on posts but see themselves outmanoeuvred in the future whenever the right ties up with the radical and far-right in votes on particular issues.

8. The turnout was 0,33 per cent higher than last time, the highest in three decades – but the elections involved only half of the voters

In 1979, when the assembly was elected for the first time directly, the turnout noted was on the level of 61,99 per cent. The subsequent European elections had been observing a decline – dropping to 42,61 per cent in 2014. Thus 2019 was the first exception with 50,66 per cent and 2024 continued, increasing the turnout however only slightly, to 50,93 per cent. Several analysts and journalists exhibit enthusiasm around that number, pointing that this is the highest turnout in three decades – a period that evidently correlates with the arrival of a new generation. But if to confront it with the fact that the past legislative period was said to have seen an unprecedented mobilisation of citizens (for example around the Conference on the Future of Europe), as also with the fact that European issues entered into the national debates (due to the developments and due to the work of leaders as Pedro Sanchez, Antonio Costa or Saana Marin in particular) – the final result is not reassuring at all.

There are institutional and political answers to consider, if one accepts that by the time the polling stations close for one election, the campaign for the next one kicks off already. The institutional answers can be found in the reform of the electoral rules, which project Social Democrats have been at the leadership of. And combining them with a larger commitment to a democratic reform of the Union, that should include such actions as reinforcing mechanisms to boost consultative and deliberative democracy. An example here is a revised approach to citizens’ panels and assemblies. The political answer is, as always, more complex. The political polarisation described in the previous points is an outcome of growing divides and shifts within the electorates. Age, gender, income, place of residence and level education matter a great deal, segmenting the societies – and making it very difficult to come up with sound political synthesis that would bridge among these groups. That is especially when it comes to a pan-European narrative. Negligence in addressing these divides is bound to have grave consequences however, fuelling conflicts. Especially intergenerational ones, but also inter-gender ones that will shape the politics of the future. There is a clear split with young men having gone to vote far right and young women leaning progressive.

9. There were protests that may be inducing backlash, while there was little when it comes to creative, forward-looking deliberations to counterbalance them

Throughout the decades, the Brussels bubble grew a certain suppleness in dealing with protests that now and then reach the EU capital. The mobilisations of different types bring activists of diverse causes to Schuman Square or Place Luxembourg. And though it may not seem so from the reactions of those who pass by on their way to work in the institutions, they serve as an important reminder about issues relevant to the European public. Sometimes they even service as an incentive to elevate a matter to a legislative question. In the season ahead of the European elections 2024, the most prominent mobilisations were those of the farmers. First because of their scale and outreach, secondly because of their frequent repetitions, and third because of the influence they succeeded in getting hold of. In response to them, the EPP backed off from some of the earlier commitments, and started blurring its position on the new MFF (Multiannual Financial Framework) and the future of the CAP (Common Agriculture Policy).

Even though the decisions on these matters are questions for the future, the initial responses from the right side of the aisle indicate a willingness to accommodate the demands and walk back on some of the agreements (concerning the European Green Deal for example). That would be a regress of already decided parts of the EU agenda. There is a fundamental question if in parallel to the famrers’ protests there was a space and the ideas developed outside of the political parties that would point to possible progress. It seems that the only other project with a pan-European outreach that is getting recognition (while using a very different toolbox to rally support at present) is the project of an ECI (European Citizens Initiative) to make the EU guarantee access to safe and free abortion to everyone in Europe. And there is a worry that it may face obstacles, when entangled with the still not completed project of the Health Union and then brought down with an excuse of the EU lacking competences in the field. These observations about civic mobilisations should serve as motivation for the next mandate to put more efforts in developing spaces for deliberative democracy and find ways in which political creativity, which can counterbalance the backlash, will not be right away cropped by existing legislative limitations.

10. Social Democracy is the second force in the European Parliament, but the result should become a motivation to aspire for more

The PES family entered the campaign underlining the crucial moment in which the EU found itself and enlisting key decisions that they wanted to win citizens’ support for. Summing up the results in the member states they sustained the position of the second largest group in the European Parliament, which however will be a very different assembly in composition and in the dynamic of the debates. To that end, the internal EP struggles will also play differently in the new political context that emerged within the European Council and in the relation with the new European Commission (that will represent some attempt a new type of political rebalancing). All in all, there will be much in the mechanics to be preoccupied with and little space for longer-term thinking.

At this stage there is no reason not to believe that the Social Democrats would not succeed in playing their hand well, ensuring at least one of the top jobs, claiming relevant portfolios in the Commission and agreeing on some red lines in the Commission Work Plan. They have done so in the past, and, numerically speaking, the new circumstances should permit them to do the same. Being part of a large pro-European coalition brings about a challenge of constituting part of an amalgamate. And that would be particularly perilous, in the circumstances of progressing polarisation of the European politics. This is also while the results in 2024 allow to stand tall on the EU level, they also suggest a need for a deeper reflection. First about the Social Democratic family, the ways to renew it (or even revive in some places), strengthening its profile and mobilising capacities. Secondly, about their European cooperation and the unique project they want to unite behind. It is clear that it must be one envisaging an open, globally relevant Union, capable of autonomous action, but it also must be one that responds to people’s preoccupations with the cost-of-living crisis and shows the path to social progress. The next years will be crucial in defining a new industrial strategy, pursuing the social cohesion and pursuing the agenda of the European Pillar of Social Rights. As also in claiming ownership over new issues, for which there should be a pre-existing energy – especially that almost half of the S&D MEPs are new to the EP. And thirdly, there must be a strategic reflection on the potential future coalitions. It is true that S&D stayed fairly the same in numbers, but the Greens and other left-wing parties dropped substantially. This is a warning, especially when so many voters declare affinity with an agenda that is progressive in nature at the same time. For them, Social Democrats have to become the first choice again, in order to be able to choose their partners in the future rather than to be chosen.

Photo Credits: Shutterstock.com/AlexandrosMichailidis